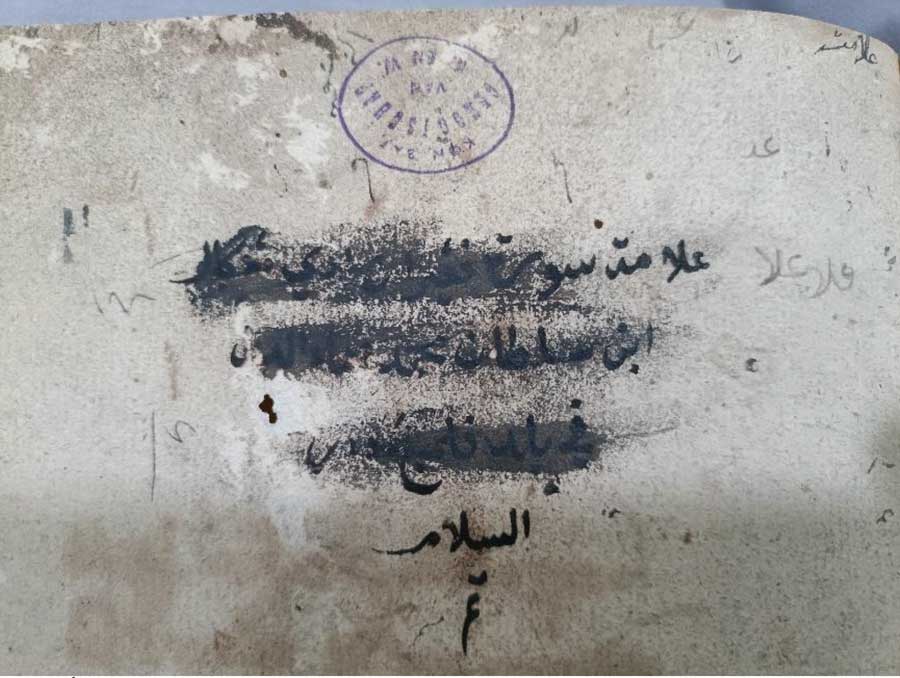

Figure 1. PNRI KBG 185 Panji (also known as Hikayat Candra Kirana, a popular name in Palembang), f. 1r, statement of ownership.

Where did the Palembang Kraton manuscripts go? A trace of the royal collection in a lending library

by Alan Darmawan

In his cynical report describing the river city of Palembang and the rule of the sultanate, Beschrijving van de Hoofdplaats van Palembang, the Dutch commissary J.J. van Sevenhoven admitted that Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin was an exception in terms of literacy. He stated that Sultan Mahmud “had eene vrij uitgestrekte bibliotheek” (1823: 80), or an extensive library. From the viewpoint of a European, the “bibliotheek” might imply a house of books or a room to store an “extensive” collection of books. Unfortunately, Van Sevenhoven did not describe the physical setting of the palace library or what its collection contained. The library itself seemed to have been empty when the commissary observed it. Only after hunting for the sultan’s treasure throughout the town of Palembang, did he discover 55 manuscripts, which he confiscated and sent to Batavia. Some of these were transferred to the Batavia Society in 1822, and are now held by the National Library of Indonesia (Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia/PNRI). Other manuscripts seized during the British attack on Palembang in 1812 were acquired by Thomas Stamford Raffles and by William Marsden, ending up in the libraries of the Royal Asiatic Society and SOAS University of London, respectively. Yet others are scattered across other institutions.

But did any manuscripts remain in Palembang? And, if there were, what happened to them? Recent documentation and digitisation by DREAMSEA and EAP have revealed that some manuscripts are now owned by the descendants of Palembang nobles and religious scholars. But perhaps the most intriguing trajectory is that of the manuscripts that passed from the royal library into non-elite hands, including local commercial lending libraries. This kind of library thrived in Palembang in the late 19th century to early 20th century, as discussed by Ulrich Kratz (1980, 1977).

A PNRI manuscript, KBG 185, records a trace of the royal collection of Palembang that escaped the palace and went to a local lending library, finally ending up in the Batavia Society in the 1880s, acquired “from a Dutch commissioner in Palembang” (Drewes 1977: 203). This manuscript contains a Panji story with East Javanese language and was copied in 1801 by order of a Palembang Prince, Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin’s brother, Pangeran Adi Menggala. A note in the manuscript KBG 185 reads “Alamat surat Pangeran Adi Menggala ibn Sultan Muhammad Baha’uddin fi balad Palembang Darussalam.” The owner of the book was also known as Pangeran Adipati, one of the Palembang Sultan’s sons who later ruled as Sultan Ahmad Najamuddin. The change of ownership can be seen in the attempt to efface the note with black ink (Figure 1, above).

Another note on the last two pages of the manuscript again shows a later owner’s hand (pp. 352-353). This owner apparently lent the book to readers, as the note outlines the rules of borrowing. In a form of Malay syair, it warns the readers to handle the book with a great care: not to read it close to an oil lamp, not to fold up its pages, not to put wet betel leaves in it, not to tear the papers apart, and to return it after four days maximum. The writer of the note explains that this is because Dutch paper is expensive, and urges the borrower to not take it lightly lest they be insulted or scolded. Below is an excerpt of the note.

Jikalau tak hendak beroleh nista

Tuan hematkan nyata1

Jangan dilipat jangan dipata

Jangan dibaca dakat pelita

If you don’t want to be insulted,

Gentlemen, this has to be considered:

The pages are not to be folded,

Don’t read it beside an oil lamp.

Sebab demikian kami berkata

Bukannya sayang kepada harta

Jika tertituk minyak pelita

Menjadi hina pemandangan mata

The reasons for me to speak are

Not from love of property [but]

When the book is dripped on by lamp oil

It will be poor in our sight.

Hamba karangkan suatu madah

Ingat2 orang yang muda

Jikalau bukan ayah dan bundah

Hartanya jangan tuan permuda

I composed this utterance

To remind young people:

If it does not belong to your parents

Don’t treat this property with ignorance.

Zaman sekarang suda termasa

Banyaklah tuan periksa

Jangan diselitkan sirih yang basa

Itupun memberi surat binasa

Today’s age has shown proof:

Gentlemen, be attentive.

Don’t insert a wet betel leaf,

For that will destroy the book.

Ayu mas dewa kesuma

Bunga seroja kembang di lema

Surat nan jangan dipinjam lama

Empat hari hanya [kah] kelima

O noblemen and women,

The lotus blossoms on the ground.

This book is not for long-term rent,

Only four days, on the fifth [return it].

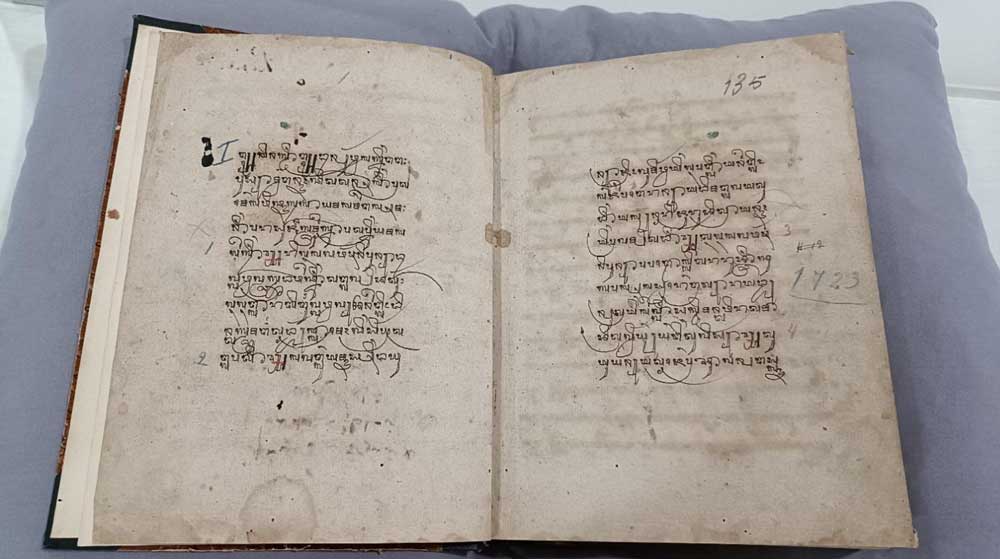

Figure 2. PNRI KBG 185 Hikayat Candra Kirana, [p. 352]. A note in Jawi on the rules of borrowing.

This kind of note reflects an effort to educate the customers in borrowing etiquette at the time of the emergence of lending library, a ‘public’ library that grew a readership in the kampung community. Though these notes are in Jawi script and Malay language, the main text is in Hanacaraka script and Javanese language (Figures 2 and 3). This aspect of the manuscript suggests that readers in Palembang in the 19th century were able to read both scripts and both languages, perhaps because of the dispersal of royal books writen in Jawi and Javanese to ordinary people. This may explain how Javanese, the official language of the royal court of Palembang, could be read by the customers of a lending library in a Palembang kampung in the late 19th century. So although the colonial spoliation of the Palembang palace library removed many manuscripts, an unexpected side effect was the dispersal of some to the local community. What effect this may have had on literary production in Palembang remains to be discovered.

Figure 3. First two pages of the manuscript KBG 185.

Alan Darmawan is a Postdoctoral Researcher at SOAS University of London.

Footnotes

- Some peculiar spellings deserve an explanation. Some words do not use ‘h’ ending as understood by a modern reader, including pata (broken), permuda (take it lightly), basa (wet), lema (Jav: soil), luda (saliva). Whereas, the word for mother has an ‘h’ in the end as (bundah). A peculiar spelling like tituk for titik (drop of liquid) might reflect local usage. In addition, syllables/particles in square bracket are there in the original text but can be omitted for a clearer line. The whole note consists of 13 four-line stanzas. Beside there are 2 two-line verses that are not rhymed but seem to give an emphasis in its appeal to readers to follow the rules.